Part 1 - Drawing the '@' symbol and moving it around

Welcome to part 1 of this tutorial! This series will help you create your very first roguelike game, written in Python!

This tutorial is largely based off the one found on Roguebasin. Many of the design decisions were mainly to keep this tutorial in lockstep with that one (at least in terms of chapter composition and general direction). This tutorial would not have been possible without the guidance of those who wrote that tutorial, along with all the wonderful contributors to tcod and python-tcod over the years.

This part assumes that you have either checked Part 0 and are already set up and ready to go. If not, be sure to check that page, and make sure that you’ve got Python and TCOD installed, and a file called main.py created in the directory that you want to work in.

Assuming that you’ve done all that, let’s get started. Modify (or create, if you haven’t already) the file main.py to look like this:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import tcod

def main():

print("Hello World!")

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()You can run the program like any other Python program, but for those who are brand new, you do that by typing python main.py in the terminal. If you have both Python 2 and 3 installed on your machine, you might have to use python3 main.py to run (it depends on your default python, and whether you’re using a virtualenv or not).

Alternatively, because of the first line, #!usr/bin/env python, you can run the program by typing ./main.py, assuming you’ve either activated your virtual environment, or installed tcod on your base Python installation. This line is called a “shebang”.

Okay, not the most exciting program in the world, I admit, but we’ve already got our first major difference from the other tutorial. Namely, this funky looking thing here:

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()So what does that do? Basically, we’re saying that we’re only going to run the “main” function when we explicitly run the script, using python main.py. It’s not super important that you understand this now, but if you want a more detailed explanation, this answer on Stack Overflow gives a pretty good overview.

Confirm that the above program runs (if not, there’s probably an issue with your tcod setup). Once that’s done, we can move on to bigger and better things. The first major step to creating any roguelike is getting an ‘@’ character on the screen and moving, so let’s get started with that.

Modify main.py to look like this:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import tcod

def main() -> None:

screen_width = 80

screen_height = 50

tileset = tcod.tileset.load_tilesheet(

"dejavu10x10_gs_tc.png", 32, 8, tcod.tileset.CHARMAP_TCOD

)

with tcod.context.new_terminal(

screen_width,

screen_height,

tileset=tileset,

title="Yet Another Roguelike Tutorial",

vsync=True,

) as context:

root_console = tcod.Console(screen_width, screen_height, order="F")

while True:

root_console.print(x=1, y=1, string="@")

context.present(root_console)

for event in tcod.event.wait():

if event.type == "QUIT":

raise SystemExit()

if __name__ == "__main__":

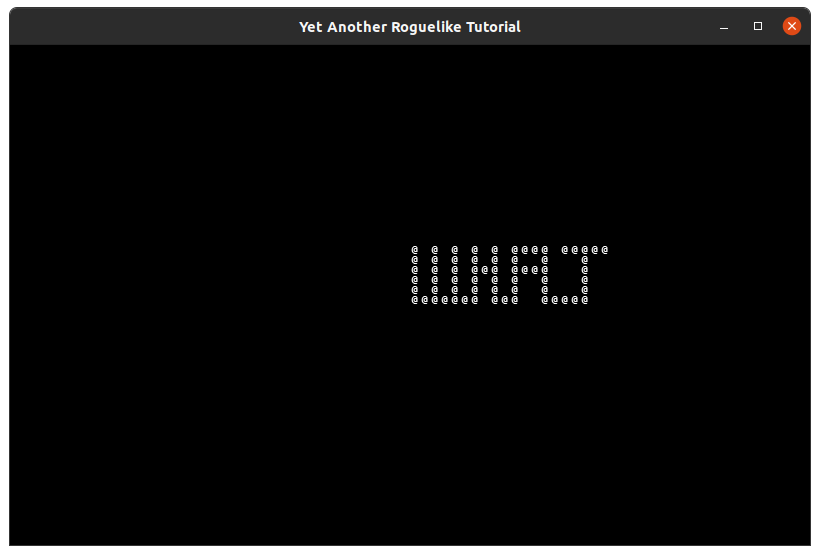

main()Run main.py again, and you should see an ‘@’ symbol on the screen. Once you’ve fully soaked in the glory on the screen in front of you, you can click the “X” in the top-left corner of the program to close it.

There’s a lot going on here, so let’s break it down line by line.

screen_width = 80

screen_height = 50This is simple enough. We’re defining some variables for the screen size.

Eventually, we’ll load these values from a JSON file rather than hard coding them in the source, but we won’t worry about that until we have some more variables like this.

tileset = tcod.tileset.load_tilesheet(

"dejavu10x10_gs_tc.png", 32, 8, tcod.tileset.CHARMAP_TCOD

)Here, we’re telling tcod which font to use. The "dejavu10x10_gs_tc.png" bit is the actual file we’re reading from (this should exist in your project folder).

with tcod.context.new_terminal(

screen_width,

screen_height,

tileset=tileset

title="Yet Another Roguelike Tutorial",

vsync=True,

) as context:This part is what actually creates the screen. We’re giving it the screen_width and screen_height values from before (80 and 50, respectively), along with a title (change this if you’ve already got your game’s name figured out). tileset uses the tileset we defined earlier. and vsync will either enable or disable vsync, which shouldn’t matter too much in our case.

root_console = tcod.Console(screen_width, screen_height, order="F")This creates our “console” which is what we’ll be drawing to. We also set this console’s width and height to the same as our new terminal. The “order” argument affects the order of our x and y variables in numpy (an underlying library that tcod uses). By default, numpy accesses 2D arrays in [y, x] order, which is fairly unintuitive. By setting order="F", we can change this to be [x, y] instead. This will make more sense once we start drawing the map.

while True:This is what’s called our ‘game loop’. Basically, this is a loop that won’t ever end, until we close the screen. Every game has some sort of game loop or another.

root_console.print(x=1, y=1, string="@")This line is what tells the program to actually put the “@” symbol on the screen in its proper place. We’re telling the root_console we created to print the “@” symbol at the given x and y coordinates. Try changing the x and y values and see what happens, if you feel so inclined.

context.present(root_console)Without this line, nothing would actually print out on the screen. This is because context.present is what actually updates the screen with what we’ve told it to display so far.

for event in tcod.event.wait():

if event.type == "QUIT":

raise SystemExit()This part gives us a way to gracefully exit (i.e. not crashing) the program by hitting the X button in the console’s window. The line for event in tcod.event.wait() will wait for some sort of input from the user (mouse clicks, keyboard strokes, etc.) and loop through each event that happened. SystemExit() tells Python to quit the current running program.

Alright, our “@” symbol is successfully displayed on the screen, but we can’t rest just yet. We still need to get it moving around!

We need to keep track of the player’s position at all times. Since this is a 2D game, we can express this in two data points: the x and y coordinates. Let’s create two variables, player_x and player_y, to keep track of this.

...

screen_height = 50

+

+ player_x = int(screen_width / 2)

+ player_y = int(screen_height / 2)

+

tileset = tcod.tileset.load_tilesheet(

"dejavu10x10_gs_tc.png", 32, 8, tcod.tileset.CHARMAP_TCOD

)

...

...

screen_height = 50

player_x = int(screen_width / 2)

player_y = int(screen_height / 2)

tileset = tcod.tileset.load_tilesheet(

"dejavu10x10_gs_tc.png", 32, 8, tcod.tileset.CHARMAP_TCOD

)

...

Note: Ellipses denote omitted parts of the code. I’ll include lines around the code to be inserted so that you’ll know exactly where to put new pieces of code, but I won’t be showing the entire file every time. The green lines denote code that you should be adding.

We’re placing the player right in the middle of the screen. What’s with the int() function though? Well, Python 3 doesn’t automatically

truncate division like Python 2 does, so we have to cast the division result (a float) to an integer. If we don’t, tcod will give an error.

Note: It’s been pointed out that you could divide with // instead of / and achieve the same effect. This is true, except in cases where, for whatever reason, one of the numbers given is a decimal. For example, screen_width // 2.0 will give an error. That shouldn’t happen in this case, but wrapping the function in int() gives us certainty that this won’t ever happen.

We also have to modify the command to put the ‘@’ symbol to use these new coordinates.

...

while True:

- root_console.print(x=1, y=1, string="@")

+ root_console.print(x=player_x, y=player_y, string="@")

context.present(root_console)

...

...

while True:

root_console.print(x=1, y=1, string="@")

root_console.print(x=player_x, y=player_y, string="@")

context.present(root_console)

...

Note: The red lines denote code that has been removed.

Run the code now and you should see the ‘@’ in the center of the screen. Let’s take care of moving it around now.

So, how do we actually capture the user’s input? TCOD makes this pretty easy, and in fact, we’re already doing it. This line takes care of it for us:

for event in tcod.event.wait():It gets the “events”, which we can then process. Events range from mouse movements to keyboard strokes. Let’s start by getting some basic keyboard commands and processing them, and based on what we get, we’ll move our little “@” symbol around.

We could identify which key is being pressed right here in main.py, but this is a good opportunity to break our project up a little bit. Sooner or later, we’re going to have quite a few potential keyboard commands, so putting them all in main.py would make the file longer than it needs to be. Maybe we should import what we need into main.py rather than writing it all there.

To handle the keyboard inputs and the actions associated with them, let’s actually create two new files. One will hold the different types of “actions” our rogue can perform, and the other will bridge the gap between the keys we press and those actions.

Create two new Python files in your project’s directory, one called input_handlers.py, and the other called actions.py. Let’s fill out actions.py first:

class Action:

pass

class EscapeAction(Action):

pass

class MovementAction(Action):

def __init__(self, dx: int, dy: int):

super().__init__()

self.dx = dx

self.dy = dyWe define three classes: Action, EscapeAction, and MovementAction. EscapeAction and MovementAction are subclasses of Action.

So what’s the plan for these classes? Basically, whenever we have an “action”, we’ll use one of the subclasses of Action to describe it. We’ll be able to detect which subclass we’re using, and respond accordingly. In this case, EscapeAction will be when we hit the Esc key (to exit the game), and MovementAction will be used to describe our player moving around.

There might be instances where we need to know more than just the “type” of action, like in the case of MovementAction. There, we need to know not only that we’re trying to move, but in which direction. Therefore, we can pass the dx and dy arguments to MovementAction, which will tell us where the player is trying to move to. Other Action subclasses might contain additional data as well, and others might just be subclasses with nothing else in them, like EscapeAction.

That’s all we need to do in actions.py right now. Let’s fill out input_handlers.py, which will use the Action class and subclasses we just created:

from typing import Optional

import tcod.event

from actions import Action, EscapeAction, MovementAction

class EventHandler(tcod.event.EventDispatch[Action]):

def ev_quit(self, event: tcod.event.Quit) -> Optional[Action]:

raise SystemExit()

def ev_keydown(self, event: tcod.event.KeyDown) -> Optional[Action]:

action: Optional[Action] = None

key = event.sym

if key == tcod.event.K_UP:

action = MovementAction(dx=0, dy=-1)

elif key == tcod.event.K_DOWN:

action = MovementAction(dx=0, dy=1)

elif key == tcod.event.K_LEFT:

action = MovementAction(dx=-1, dy=0)

elif key == tcod.event.K_RIGHT:

action = MovementAction(dx=1, dy=0)

elif key == tcod.event.K_ESCAPE:

action = EscapeAction()

# No valid key was pressed

return actionLet’s go over what we’ve added.

from typing import OptionalThis is part of Python’s type hinting system (which you don’t have to include in your project). Optional denotes something that could be set to None.

import tcod.event

from actions import Action, EscapeAction, MovementActionWe’re importing tcod.event so that we can use tcod’s event system. We don’t need to import tcod, as we only need the contents of event.

The next line imports the Action class and its subclasses that we just created.

class EventHandler(tcod.event.EventDispatch[Action]):We’re creating a class called EventHandler, which is a subclass of tcod’s EventDispatch class. EventDispatch is a class that allows us to send an event to its proper method based on what type of event it is. Let’s take a look at the methods we’re creating for EventHandler to see a few examples of this.

def ev_quit(self, event: tcod.event.Quit) -> Optional[Action]:

raise SystemExit()Here’s an example of us using a method of EventDispatch: ev_quit is a method defined in EventDispatch, which we’re overriding in EventHandler. ev_quit is called when we receive a “quit” event, which happens when we click the “X” in the window of the program. In that case, we want to quit the program, so we raise SystemExit() to do so.

def ev_keydown(self, event: tcod.event.KeyDown) -> Optional[Action]:This method will receive key press events, and return either an Action subclass, or None, if no valid key was pressed.

action: Optional[Action] = None

key = event.symaction is the variable that will hold whatever subclass of Action we end up assigning it to. If no valid key press is found, it will remain set to None. We’ll return it either way.

key holds the actual key we pressed. It doesn’t contain additional information about modifiers like Shift or Alt, just the actual key that was pressed. That’s all we need right now.

From there, we go down a list of possible keys pressed. For example:

if key == tcod.event.K_UP:

action = MovementAction(dx=0, dy=-1)In this case, the user pressed the up-arrow key, so we’re creating a MovementAction. Notice that here (and in all the other cases of MovementAction) we provide dx and dy. These describe which direction our character will move in.

elif key == tcod.event.K_ESCAPE:

action = EscapeAction()If the user pressed the “Escape” key, we return EscapeAction. We’ll use this to exit the game for now, though in the future, EscapeAction can be used to do things like exit menus.

return actionWhether action is assigned to an Action subclass or None, we return it.

Let’s put our new actions and input handlers to use in main.py. Edit main.py like this:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import tcod

+from actions import EscapeAction, MovementAction

+from input_handlers import EventHandler

def main() -> None:

screen_width = 80

screen_height = 50

player_x = int(screen_width / 2)

player_y = int(screen_height / 2)

tileset = tcod.tileset.load_tilesheet(

"dejavu10x10_gs_tc.png", 32, 8, tcod.tileset.CHARMAP_TCOD

)

+ event_handler = EventHandler()

with tcod.context.new_terminal(

...

...

for event in tcod.event.wait():

- if event.type == "QUIT":

- raise SystemExit()

+ action = event_handler.dispatch(event)

+ if action is None:

+ continue

+ if isinstance(action, MovementAction):

+ player_x += action.dx

+ player_y += action.dy

+ elif isinstance(action, EscapeAction):

+ raise SystemExit()

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

#!/usr/bin/env python3 import tcod from actions import EscapeAction, MovementAction from input_handlers import EventHandler def main() -> None: screen_width = 80 screen_height = 50 player_x = int(screen_width / 2) player_y = int(screen_height / 2) tileset = tcod.tileset.load_tilesheet( "dejavu10x10_gs_tc.png", 32, 8, tcod.tileset.CHARMAP_TCOD ) event_handler = EventHandler() with tcod.context.new_terminal( ... ... for event in tcod.event.wait(): if event.type == "QUIT": raise SystemExit() action = event_handler.dispatch(event) if action is None: continue if isinstance(action, MovementAction): player_x += action.dx player_y += action.dy elif isinstance(action, EscapeAction): raise SystemExit() if __name__ == "__main__": main()

Let’s break down the new additions a bit.

from actions import EscapeAction, MovementAction

from input_handlers import EventHandlerWe’re importing the EscapeAction and MovementAction from actions, and EventHandler from input_handlers. This allows us to use the functions we wrote in those files in our main file.

event_handler = EventHandler()event_handler is an instance of our EventHandler class. We’ll use it to receive events and process them.

action = event_handler.dispatch(event)We send the event to our event_handler’s “dispatch” method, which sends the event to its proper place. In this case, a keyboard event will be sent to the ev_keydown method we wrote. The Action returned from that method is assigned to our local action variable.

if action is None:

continueThis is pretty straightforward: If action is None (that is, no key was pressed, or the key pressed isn’t recognized), then we skip over the rest the loop. There’s no need to go any further, since the lines below are going to handle the valid key presses.

if isinstance(action, MovementAction):

player_x += action.dx

player_y += action.dyNow we arrive at the interesting part. If the action is an instance of the class MovementAction, we need to move our “@” symbol. We grab the dx and dy values we gave to MovementAction earlier, which will move the “@” symbol in which direction we want it to move. dx and dy, as of now, will only ever be -1, 0, or 1. Regardless of what the value is, we add dx and dy to player_x and player_y, respectively. Because the console is using player_x and player_y to draw where our “@” symbol is, modifying these two variables will cause the symbol to move.

elif isinstance(action, EscapeAction):

raise SystemExit()raise SystemExit() should look familiar: it’s how we’re quitting out of the program. So basically, if the user hits the Esc key, our program should exit.

With all that done, let’s run the program and see what happens!

Indeed, our “@” symbol does move, but… it’s perhaps not what was expected.

Unless you’re making a roguelike version of “Snake” (and who knows, maybe you are), we need to fix the “@” symbol being left behind wherever we move. So why is this happening in the first place?

Turns out, we need to “clear” the console after we’ve drawn it, or we’ll get these leftovers when we draw symbols in their new places. Luckily, this is as easy as adding one line:

...

while True:

root_console.print(x=player_x, y=player_y, string="@")

context.present(root_console)

+ root_console.clear()

for event in tcod.event.wait():

...

...

while True:

root_console.print(x=player_x, y=player_y, string="@")

context.present(root_console)

root_console.clear()

for event in tcod.event.wait():

...

That’s it! Run the project now, and the “@” symbol will move around, without leaving traces of itself behind.

That wraps up part one of this tutorial! If you’re using git or some other form of version control (and I recommend you do), commit your changes now.

If you want to see the code so far in its entirety, click here.